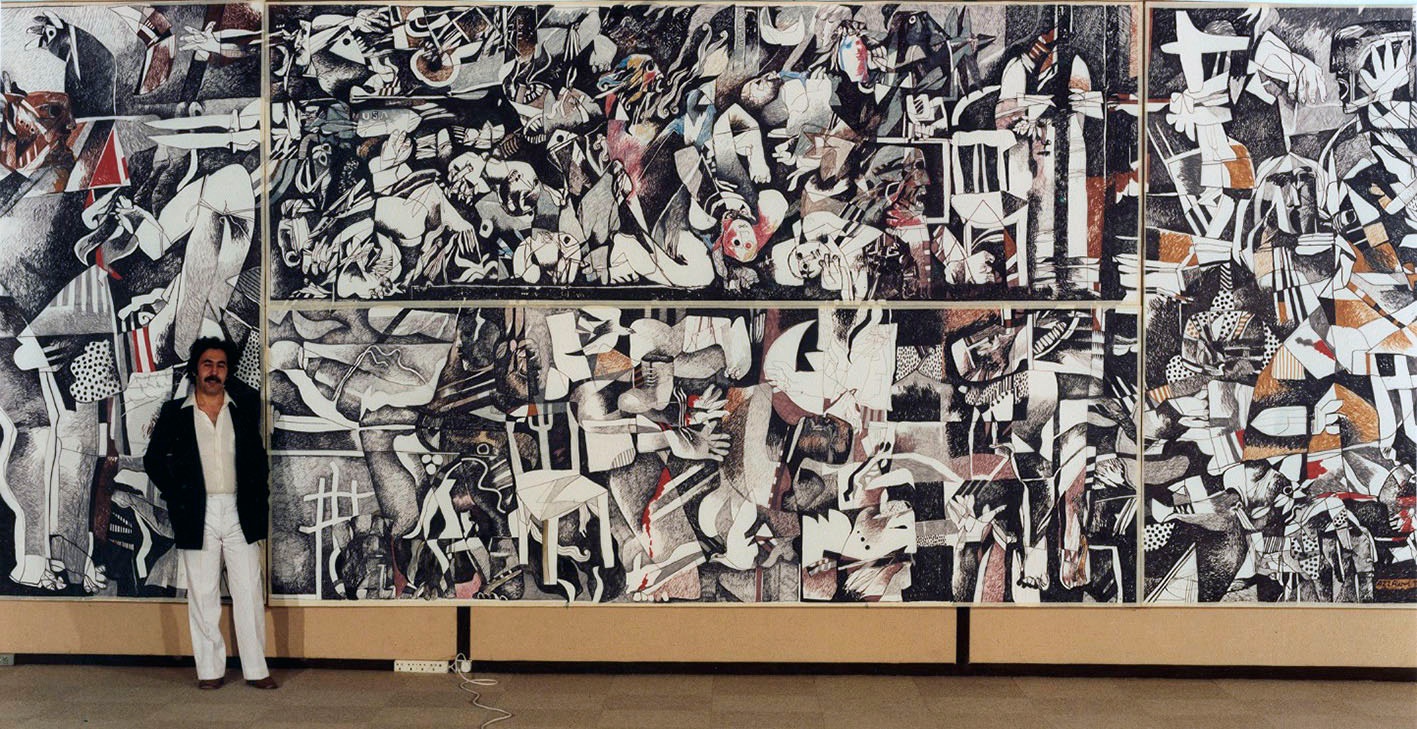

Earlier this year, London’s Tate Modern acquired “Sabra and Shatila Massacre” (1982-83), an epic mural-sized drawing by pioneering Iraqi artist Dia al-Azzawi. Sprawling as it is towering and engulfing, the artist began the massive work after news surfaced that between two and three thousand Palestinian and Lebanese civilians were strategically murdered in and around the refugee camps of southern Beirut in 1982. While creating “Sabra and Shatila Massacre,” al-Azzawi was also moved by Jean Genet’s “Four Hours in Shatila,” a written dispatch of the hell on earth that was the site of this civil-war era carnage, the violent details of which are impossible to take in without periodically searching for respite by turning away from the page.

Al-Azzawi recreates this frenetic energy in four large panels, establishing visions that, like Genet’s text, become immovable to the mind’s eye. Two vertical side rectangles frame a pair of larger horizontal scenes, and within these physical demarcations images are uncontained. A boot, two chairs, a plane, a “USA” missile, and barbed wire are interspersed between the ravaging expressionism of shaded forms and the darkened areas of nothingness that toss, eject, and dismember bodies until they are buried. There is no beginning or end to the composition but to the right and left of the center are two upright figures, gods of war who flank a netherworld that has already claimed its victims. Scant moments of color appear as though time has frozen into a mere memory: a ceaseless nightmare.

["Sabra and Shatila Massacre" (1982-83). Copyright Dia al-Azzawi. Image courtesy of Tate Modern.]

["Sabra and Shatila Massacre" (1982-83). Copyright Dia al-Azzawi. Image courtesy of Tate Modern.]

Within a labyrinth of death and the mundane (the remnants of domestic structures), the artist is relentless in his indictment, what he refers to as “a manifesto of dismay and anger.” Areas of white, where the eye would normally rest in a monochromatic composition, ignite horror, become corpses. Instances of Cubism are employed not to convey the dynamic movement of form but as a system of measure through which to count out cyclical disaster.

At first, this dismay and anger took on a compulsory drive as he recalled the constrictive grounds of the Beirut neighborhood and began to draw:

I had at that time a roll of paper and, without any preparatory sketches, the idea for the work came to me. I tried to visualize my previous experience of walking through this camp, with its small rooms separated by a narrow road, in the 1970s. (Art Daily, July 5, 2012)

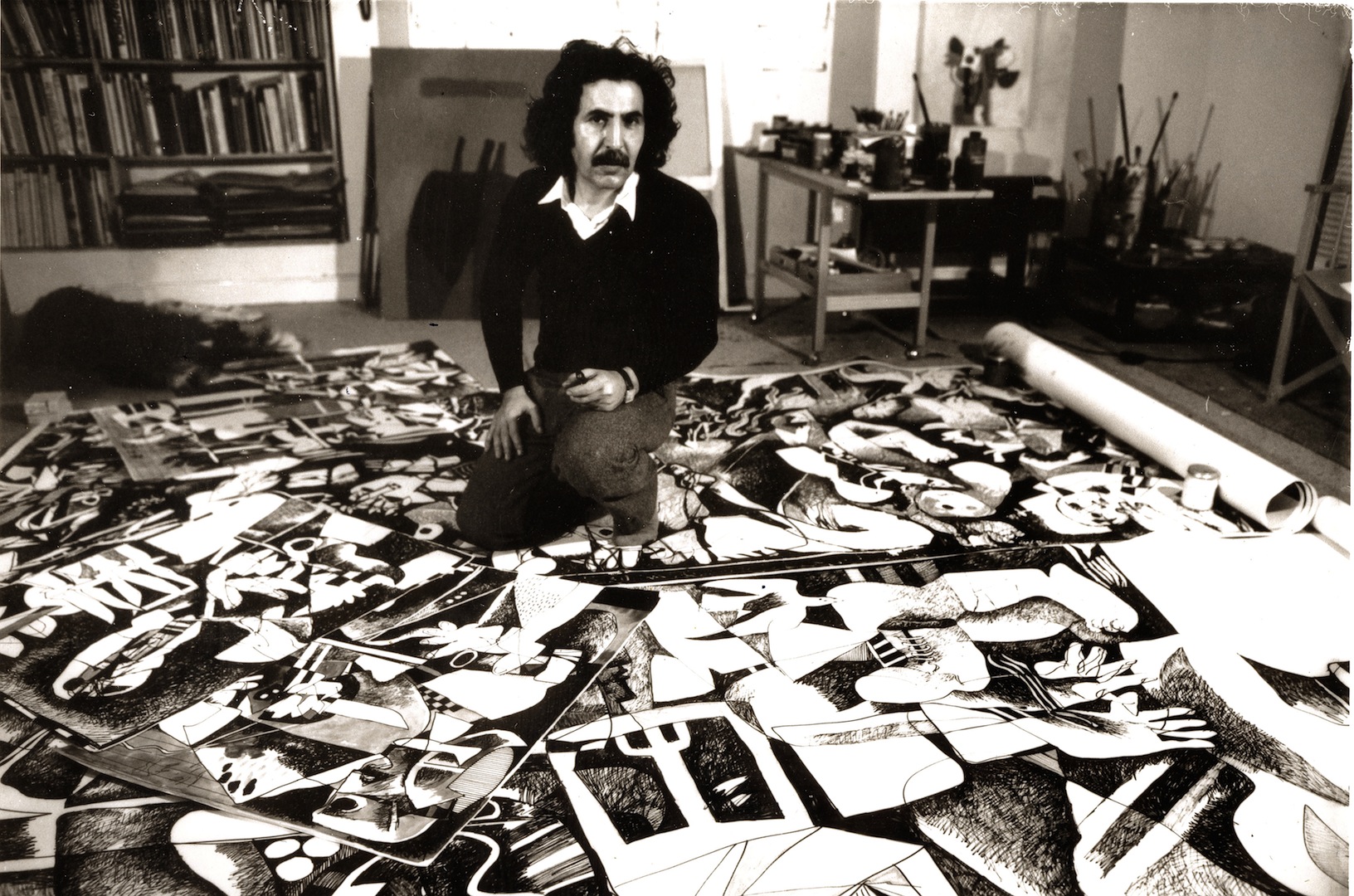

[Dia al-Azzawi in his Highgate studio, London (1983). Image courtesy of the artist.]

[Dia al-Azzawi in his Highgate studio, London (1983). Image courtesy of the artist.]

The resulting drawings were produced as micro components of a larger whole and covered the width of his London studio. These fragments (or vignettes, rather) are organized in a manner that is similar to the broken narrative structure of Genet’s writing on the subject — except that in al-Azzawi’s work there is no way out and no room for pause. When completed in 1983, the pieces were mounted onto stretchers and shown in a Kuwait gallery as part of the series We are not Seen, but Corpses, which included a set of copper engravings.

[Dia al-Azzawi at the opening of his 1983 solo exhibition in Kuwait. Image courtesy of the artist.]

[Dia al-Azzawi at the opening of his 1983 solo exhibition in Kuwait. Image courtesy of the artist.]

In “Four Hours in Shatila” Genet interrupts graphic reports of the massacre by intermittently removing his focus from the bloodstained streets of Lebanon, withdrawing to romantic portrayals of Palestinian fedayeen in Jordan ten years prior as he escapes his own haunting and divides his account into a binary tale of “love” and “death:”

These two words are quickly associated when one of them is written down. I had to go to Shatila to understand the obscenity of love and the obscenity of death. In both cases the body has nothing more to hide: positions, contortions, gestures, signs, even silences belong to one world and to the other. (Journal of Palestine Studies, Spring 1983)

Although freed from grotesque accents, al-Azzawi’s figures are siphoned by that which inhibits the ambit of love, abjection. Genet describes the abject as he passes through catastrophe without specifically identifying it, perhaps due to his propinquity to the aftermath of the mass killings:

In the middle, near them, all these tortured victims, my mind cannot get rid of this “invisible vision:” what was the torturer like? Who was he? I see him and I do not see him. He is as large as life and the only shape he will ever have is the one formed by the stances, positions, and grotesque gestures of the dead fermenting in the sun under clouds of flies.

The writer provides knowledge of the abject, the painter gives us the means of confronting that knowledge, what Aaron Kerner explains as the “visceral charge” of the rhetorical devices that are capable of deciphering the abject (Representing The Catastrophic, The Edwin Mellen Press: 2007).

The main springboard for Kerner’s study of how visual culture can lend to reckoning with unimaginable suffering and incomprehensible events is Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror (Columbia University Press: 1982), which outlines several types of abjection — all of which are rooted in primordial repression. Without delving into the depths of psychoanalysis that the latter utilizes to arrive at such definitions, abjection exists as neither subject nor object, an intangible but ever-present force that plunges reality into chaos, a realm in which reason is discarded: “that breakdown of clarity between what sustains life and the destruction of life, the boundary between life and death itself” (Kerner). It is the non-space that fuels, orders, and commits catastrophe.

For Kristeva, narcissism lies at the root of abjection and when it is swayed and untamed, the consequences are calamitous:

The abject is perverse because it neither gives up nor assumes a prohibition, a rule, or a law; but turns them aside, misleads, corrupts; uses them, takes advantage of them, the better to deny them. It kills in the name of life — a progressive despot; it lives at the behest of death — an operator in genetic experimentations; it curbs the other’s suffering for its own profit — a cynic (and a psychoanalyst); it establishes narcissistic power while pretending to reveal the abyss… Corruption is its most common, most obvious appearance. That is the socialized appearance of the abject.

There are political implications in exploring the presence of this non-space in so far as power, abjection, and catastrophe are intrinsically connected phenomena, an interdependent trinity, and in the modern history of the Arab world, it is an entity that has lurked over virtually every aspect of life.

Throughout his artistic career, which began in Baghdad in the 1960s, al-Azzawi has returned to such scenes as a quiet sage who treads through the deluge. What distinguishes this individual work, however, is the scale with which he brings forth the state of abjection that surrounds (and led to) massacre in order to oppose it. In lieu of focusing on its significance as a historical moment through realism, or the particulars of the crime, what appears is a “poetic release of drive energy,” to borrow a phrase from Kerner.

In retrospect, this energy had been building in al-Azzawi’s previous works. The Body’s Anthem (1978-79), a series of forty drawings depicting the deadly 1976 siege of the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp in northern Beirut, displays the heavily stylized forms that would guide his subsequent manifesto; and in an introduction to a collection of limited edition silk screen prints, the artist summarizes a theme that has driven his oeuvre:

The Body’s Anthem: pictures I chose of that siege. It is not a dirge, nor is it the document of a dark massacre — it is an expression that seeks to create a free memory persisting against oppression, until a time when it can exhaust oppression’s evil.

A time that will summon the blood of friends and brothers, hastening the return of the martyrs. When the nation will be bread clean of soil and blood. A space unhindered by black treachery and the nets of disguise. When feet will cross safely over beautiful times. And men will not sell their dreams. (Dar Al-Muthallath: 1980)

"Sabra and Shatila Massacre" is currently on view at the Tate Modern.

[The above post is part of Visuals in 1500 a new Jadaliyya Culture series on aesthetics.]

![[Detail of Dia al-Azzawi`s \"Sabra and Shatila Massacre.\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/detailSabra.jpg)